Highlights from the Decorative Arts Collection

By Dr. Lesley Parness, Retired MCPC Superintendent for Horticulture Education

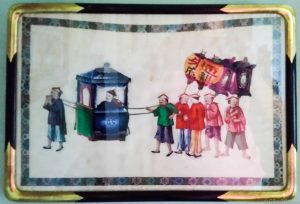

The Tubb’s brothers keen interest in the decorative arts also included the practical, everyday items of life. At Willowwood, their interest in all things Asian is reflected in statuary, paintings and even dinnerware. A cupboard near the Dining Room stores the typical family daily use Willow Ware dishes, including dinner and serving plates, cup and saucers, bowls, sugar pots, creamers and even some very sweet egg cups which we imagine held freshly laid eggs from the families chicken coop. Some are chipped, others marked with the tracery of use, they bare witness to the fact that Willow Wood was a true home, well-used and the Dining Room, the heart of it.

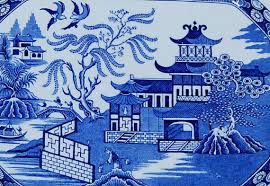

The Blue Willow pattern is one of the most recognizable tableware patterns ever produced. First introduced in England in the late 18th century, it is still popular today. The pattern evolved from Chinese landscape painting and contains multiple elements: a mandarin’s pagoda and garden; the mandarin and his hunting party on a bridge; a fisherman who rescues the lovers; the lovers’ hideaway; two birds representing the lovers; a crooked fence and, of course, the Willow.

The Chinese first produced porcelain using kaolin, a local clay. In the 13th century, Chinese craftsmen used Iranian cobalt to create a vibrant blue and white finish. It is believed that the original Willow pattern was used by the secret Hung society to communicate their propaganda and plans. Manchu rulers discovered this and destroyed all of the Willow ware they could find, but having been introduced into England by that time, it was later reintroduced into China in the 19th century.

From the late 17th to the early 18th century, England had begun importing inexpensive Chinese dinnerware, including a blue and white pattern called “Two Birds,” the “parent” of the Willow pattern. Over time, many English china producers created their own Willowware including Minton, Spode and Worchester. The “Blue Willow” china pattern became popular in Europe and America, which created a high demand for the pieces. even today, Blue Willow is a stock pattern in many stores.

The romantic legend behind the Willow pattern is said to have been invented by English pottery houses as an 18th century marketing tool. It tells of a Chinese girl from a Royal family who was promised in marriage by her father to a Duke. However, she fell in love with a lowly accountant in her father’s court. Her father was so angry that he constructed a fence around his house so his daughter could not meet with her lover. The Duke, bearing jewels as gifts, traveled to the girl’s house in a boat. The wedding was set for the day after the Willow tree shed its blossoms. On the evening of the day that the Willow shed its leaves, the lovers escaped, making off with the jewels. The two ran over a bridge and escaped to safety on an island where they lived happily for a number of years. The jilted Duke, continued searching for them and upon discovering their hiding place, he sent soldiers to capture the lovers and put them to death. The Gods then intervened and transformed the lovers into a pair of doves or lovebirds.

This Chinese poem commemorates that story:

Two birds flying high,

A Chinese vessel sailing by,

A bridge with three men, sometimes four,

A Willow tree, hanging o’er.

A Chinese temple, there it stands,

Built upon the river sands.

An apple tree, with apples on,

A crooked fence to end my song.

Can you find these design elements in these images of Willow Ware?